Do not harm the project’s code.

This was the crucial principle my seniors would stress every day when I started as a software developer. It was the same principle guiding them when they reviewed my pull requests, which would get rejected at least two or three times.

I hated it. “They’re too demanding, too critical,” I would tell myself.

But as I improved, I ended up becoming the reviewer of somebody else’s code. And I finally realized the responsibility of having to examine something written by another person.

Being a reviewer is hard. How do you make sure that the new code will benefit the project? How do you communicate that something hasn’t been addressed well without offending anybody? What is an appropriate amount of time for reviewing?

A pull request (or merge request) is the simple act of asking somebody to review your code before merging it into the working project’s base branch. But on the reviewer’s side, it can be a much more complex challenge.

Let’s analyze some best practices for reviewing pull requests, so you can become an outstanding code reviewer to the benefit of yourself, your peers, and your project.

1. Respect people’s time

A good code review process starts with respecting time. Ideally, you want to start reviewing the code within two hours after its first submission. This is mainly to appreciate the work of the person who submitted the PR.

For example, if one of your colleagues has asked you to review their work, they’ll probably wait for your review for some minutes. If the review isn’t done quickly, they’ll start working on something else.

Your colleague will create a new feature branch and start writing code for a new task. If, after four hours, you review their first code and discover it’s faulty, your colleague will have to suspend what they’re doing now to make the changes. Context switches like that can be extremely time-consuming. Depending on how your colleague works best, it might take a lot for them to recover focus when coming back to the original task.

The situation gets even worse if you let days or weeks pass by without reviewing the code. At this time, your colleague has probably even forgotten what the code was all about. There will be time wasted while they catch up with the old code, and your colleague will be more prone to introducing errors since they haven’t worked on that feature in a while.

Always respect other people’s time and work, try to be the most timely reviewer you can be, and realize that those hours your peers are waiting for your review are worth a lot.

2. Always provide constructive feedback

Even if you’re reviewing code, remember there are humans behind it. Be careful about how you may trigger other people’s emotions, especially since you’re talking about their work.

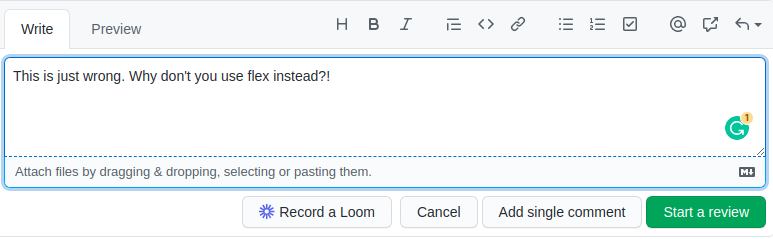

When giving feedback on an error in a pull request, adopt a constructive mindset and try to use positive language. Say “I suggest” or “You could improve X by doing Y.” Avoid “Do this” or “This is just wrong, why don’t you do Z?”

Expressing opinions with written words is very hard—be mindful of how somebody may misinterpret your suggestions and take them personally.

Make improving the code of the project your mission, but still keep in mind that the humans behind the code need to receive encouragement. In addition to keeping the workplace environment positive, this can also go a long way toward ensuring the same errors won’t be part of the next pull requests.

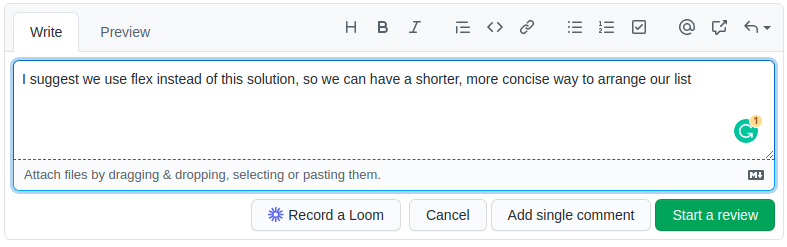

A comment you don’t want to submit.

A comment that’s a lot better!

3. Keep your ego out of code reviews

Occasionally, you’ll find yourself in a position of disagreement with the submitter’s implementation of the code or the other reviewers of a PR. Should we use this interface? Is this name appropriate for these variables?

In cases like these, you and the engineering team should aim for a culture where the best argument wins.

And remember, just because you’re a senior developer, it doesn’t mean that you’re necessarily right regarding some junior coder’s idea. Provide reasons, not feelings, to support your position to the other team members. Stay firm in your approach if you believe it’s the best one, but don’t forget to provide reasons behind everything you say. For example, link to articles or docs reinforcing your point.

If an argument gets heated, try to schedule an immediate call and positively discuss your idea. In the end, either you’ll be right or you’ll come out of the discussion with fresh knowledge.

4. Be precise about what needs to be improved

I cannot stress this point enough, as I’ve run into this so often during my career. It’s important to be clear, not only in the words you use but also in the way you construct your sentences.

Double-check every comment you write. A simple grammatical error could cause you problems.

Consider:

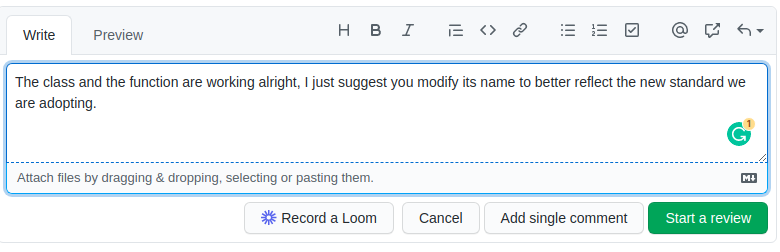

An example of confusing grammar.

What is it that needs to be changed, the class or the function? To which does it refer? And why should one of your busy peers have to ask you clarifying questions about your grammar?

Also, take care to specify the exact line you’re discussing. Don’t just mention the wrong usage of a function for adding students; what if there are two of them with very similar names, say, `addStudent` and `addStudents`?

The same applies if you submit code in a comment. It doesn’t have to be perfect, but make sure it’s still clear what you’re trying to say. Otherwise, you’re introducing your peers to a lot of confusion and frustration.

5. Don’t just hope for the code to work

Expecting the code’s author to have tested the code is fair, but you should always try it by yourself, too. Two minds are still better than one, so check out the referring branch and pull down the code locally.

Everything should build perfectly before you start testing the code. Check the functionality itself, but don’t limit yourself to simple tests. Try to cause errors. Come up with some edge cases and put the codebase to the test.

6. Reinforce code submission best practices

Remember to promote positive actions a code author can take. For example, you could enable support on GitHub for continuous integration in your project. This allows the platform to start your automated tests whenever a given event occurs (for example, whenever a PR is opened).

Continuous integration by itself encourages developers to commit code more often, it makes it easier to detect errors when they open a PR, and reduces the amount of code that needs to be debugged if something goes wrong. Frequent code updates also make it effortless to merge changes made in a pull request, so you and your team can spend more time writing code instead of resolving annoying branch conflicts.

Along the lines of running automated tests inside pull requests, don’t forget that GitHub also offers support for code coverage tools. This way, you and the code submitters will always know how much of the running code is being checked by your test suite, streamlining the review process thanks to an immediate overview of how the app is performing.

One particularly low-hanging fruit for encouraging best code submission practices is to provide your team with a well-written PR template. This is a simple text that appears whenever someone is about to open a PR, reminding developers to specify what the PR is about and what type of change has been performed (eg, bug fix, hotfix, refactor). You could even add a section for submitters to request special things for reviewers to note.

7. Be strict about temporary code

Occasionally someone will submit code that’s considered temporary. You know, the one that goes by in commit messages like hotfix or temporary refactoring for the component to work.

Don’t let the word temporary mislead you into being less strict when it comes to testing code. Short-term solutions have a magical power of becoming dirty legacy code very quickly. If you don’t want to find yourself dealing with a bigger problem in the future, always use the same discipline whether you’re reviewing a huge feature’s pull request or the tiniest of the most temporary code.

8. Check the project’s satellite files

Every medium to large-size project will bring with it hundreds of files gravitating around the code structure itself. I like to refer to them as satellite files. These include documentation, tests, and configuration files.

Remember to check these files, as they’re usually updated as often as the code and just as important. For example, verify that tests have been added for a new feature if you have them in your application.

If a function or class has been refactored, the documentation should be, too, if that’s your workflow. Similarly, build files should reflect the changes made to the project or the single files, and the changelog should always reflect the operations that have been performed on the product.

9. Visualize the bigger picture

This is the biggest lesson that those senior developers actually taught me. Code is not the line you write, but how the line integrates with and provides benefit to the application itself.

Will this change benefit the project in terms of maintenance? Will we have to change it because it’s just not scalable? Will me and my peers be able to read this code six months from now?

A pull request is never a stand-alone event. It’s one brick in a more extensive, complicated system. Keep the best practices in mind, and let them guide you toward deciding if this modification is a “approve” or “reject” one.

Summary

Reviewing somebody else’s code is a difficult task. You need to approach it efficiently, while keeping in mind that you’re a professional with responsibilities not only toward the project but toward your peers as well.

It took me a while to understand why my colleagues were so picky when it came to performing code reviews, but once I found myself in their shoes, it all became clear. Since then, the principle of not harming the code has stayed with me, and it’s guided me toward some of the best decisions I could make for each project.

Besides the nine best practices I touched on in this article, teams that are managing a lot of pull requests in GitHub should also think seriously about backing up their content. That’s where a tool like Rewind’s Backups for GitHub can help you ensure that even if GitHub goes down or a repository is mistakenly deleted, you can keep a record of your pull requests, reviews, and comments. Rewind allows you to restore deleted or altered repositories right back into GitHub, letting you get back to work faster.